by

Asa R. Gordon

Executive Director

Douglass Institute of Government

(Dedicated to the Scott Family)

This document helps to explain the contemporary confusion and controversy as to the dates on which William A. Scott III took his photographs of African-American soldiers at the liberation of the Buchenwald concentration camp.

In an interview with Col. Fuller, now retired, he

acknowledged that these records of command orders resolve the question

of Scott's probable arrival time at the Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

Fuller noted that Sgt. Bass and Sgt. Scott, as members of the

Headquarters company of the 183rd Eng. C. Bn., were "responsible for

knowing the engineer situation as far to the front as they could

travel, and it was customary for them to be far out in front of

Battalion headquarters on engineer reconnaissance in preparation for

our moving forward into new areas...Sgt. Scott was also our

headquarters photographer and Sgt. Bass had a responsibility for

establishing our water supply points".

At 2:30pm on the same day that the order for the

reassignment of the 183rd Eng. C. Bn. had been issued, elements of the

9th Armored Infantry Battalion of the 6th Armored Division under the

command of the 20th Corps were reported to be "10 kilometers due north

of Weimar". The late Captain Fred Keffer(later to become Dr. Frederick

Keffer, head of the Physics Department at the University of Pittsburgh)

of Combat Team 9 was ordered to leave a line of attack between

HOTTELSTEDT and WEIMAR, Germany and lead a 4-

man reconnaissance patrol to investigate a report by refugees on the

existence of a nearby German death camp. The patrol encountered the

concentration camp at Buchenwald.

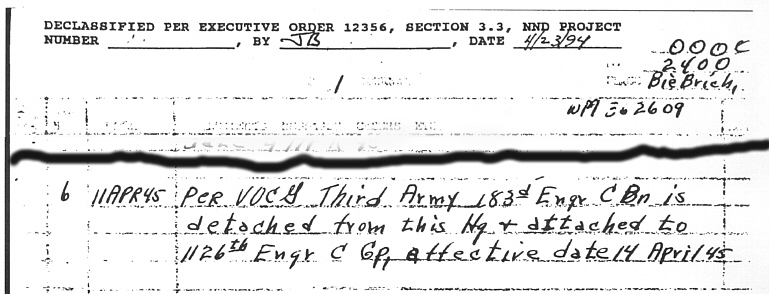

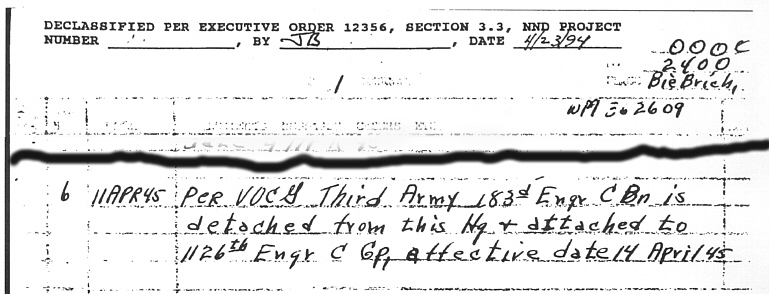

At this point we move a few days ahead in the story to clarify why Col. Fuller had expressed earlier doubts (before being exposed to the present records) about the arrival date of Sgt. Scott and Sgt. Bass at Eisenach. In his review of a pamphlet published by Scott, entitled "World War II Veteran Remembers the Horror of the Holocaust," he had noted that Scott "... speaks of riding into Eisenach on April 11th, then being instructed to go on to Weimar and Buchenwald, and then speaks of wondering whether before entering Buchenwald he should `go back to Eisenach to establish our Battalion Headquarters'. The record I have shows that we did not open our headquarters in Eisenach until April 14." In my interview with Col. Fuller, he acknowledged that the apparent discrepancy was explained further by the following newly available records.

On the 13th of April at 9:30am, the Headquarters Company of the 1126 Eng. C. Gp. departed Unterhaun and arrived at Eisenach at 11:30am. Lt. Col. Fuller transmitted the following message at 2:30pm: "183 Bn established liaison preparatory to joining 1126 Gp." The message also included the action he was to take. Lt. Col. Fuller was "Ordered to establish CP(command post) at Hersfeld by 14 1800." On April 14th at 9:00am Lt. Col. Fuller received the following message by courier: "183rd Bn Ordered to est CP at Eisenach instead of Hersfeld by 150800 Apr." On April 14th Lt. Col. Fuller transmitted the following message: "183 reported closure Bn CP at Eisenach."

Lt. Col. Fuller acknowledges that the records he has in his personal possession " are incomplete and many dates are missing. The originals of the operational reports were forwarded daily to our next higher headquarters and not retained by us." However, the aforementioned records contemporary with the events in question establish that: (1) Lt. Col. Fuller himself had arranged for liaison (Sgt. Scott and Sgt. Bass) with the Engineer Combat Group prior to the date that the main body of the 183rd was to join that unit. (2) The Quartering Party of that unit, including several trucks of the 183rd, arrived at Eisenach on April 12th. (3) Lt. Col. Fuller himself was under initial orders to establish a command post (CP) at Hersfeld. (4) Lt. Col. Fuller only became aware that he was to setup his CP at Eisenach on the 14th, which is the date of closure and the only date that is a part of his personal records. Thus, Sgt. Bass and Sgt. Scott were aware that Eisenach would be the base for headquarters before Lt. Col. Fuller, and they arrived there before Fuller came with the main body.

It should be noted that what Lt. Col. Fuller has reported elsewhere was an honest account based on his meager records, but it has often been published selectively, taken out of context, and even deliberately misrepresented in media reports. Lawrence J. Fuller, now Major General, United States Army, Retired, was on record even before my disclosure of the foregoing contemporary records of WWII, as saying: "It is also reasonable, although I have no documentation of it, that the 183rd established a water supply point for use by the concentration camp at either Ohrdruf or Buchenwald and that we were levied upon to provide transportation to remove camp residents. Under the informal arrangements then in effect there might well be no formal record of such work. If concentration camp survivors saw black American troops soon after their liberation, it seems reasonable that these could have been members of the 183rd Bn."

It has been reported elsewhere that "At the National Archives at Suitland, Maryland, there is no file devoted exclusively to the 183rd". This is false. The exclusive records for the 183rd are filed under Record Group 407, Vol.33, ENBN-183 -0.##. However, unit records for the month in question, April 1945, are missing. The explanation for the missing records and the significance of the records I did find are another story.

On April 12th, 1945 at 10:30am, Sgt. Scott and Sgt. Bass, along with the convoy of the 1126th Eng. C Gp. quartering party and several 183rd three-quater-ton trucks, arrived at Eisenach, Germany approximately 62 miles from the Buchenwald concentration camp. The former Sgt. Bass is now Leon Bass, Ph.D., a retired Philadelphia public school principal who has been lecturing on the Holocaust since 1968. In an interview I conducted with Dr. Bass, he told how they arrived at Eisenach and were setting up their tents in the bivouac area when they were approached by a lieutenant who said, "Come with me." Bass recalls, "We were ordered to proceed to Weimar. I asked the lieutenant, `Sir, where are we going?' And he said, `We're going to a concentration camp.' I didn't know what he was talking about. I had no idea what a concentration camp was all about. But on that day I was to get the shock of my life, you see. Because I was going to walk through the gate of a concentration camp called Buchenwald."

In his pamphlet "World War II Veteran Remembers the Horror of the Holocaust," William A. Scott, III discribes what happened when they arrived at Buchenwald. "We got out of our vehicles and some began to beckon to us to follow and see what had been done in that place - they were walking skeletons. The sights were beyond description. ... I had thought no place could be this bad. I took out my camera and began to take some photos - but that only lasted for a few pictures. As the scenes became more gruesome, I put my camera in its case and walked in a daze with the survivors, as we viewed all forms of dismemberment of the human body."

Scott describes an incident that occurred after they entered Buchenwald which indicates how early they must have arrived at the concentration camp after its initial discovery. "An SS trooper had remained until the day of our arrival and survivors had captured him as he tried to flee over a fence. He was taken into a building where two men from my unit followed. They said he was trampled to death by the survivors." Scott expressed a sentiment that is shared by many veterans who were witness to these camps. "I began to realize why few, if any, persons would believe the atrocities I had seen. HOLOCAUST was the word used to describe it - but one has to witness it to even begin to believe it."

Now that the American Army had discovered Buchenwald, certain tasks had to be performed as part of the mission of an engineer combat battalion. Daily summaries prepared by G-5 (military government) for mid-April described these functions. G-5 Daily Summary No. 87, from 120800 April 1945 to 140800 April 45, contains the following entry: "DP [displaced person] Team No 10 is operating in Buchenwald Concentration Camp.... Health conditions very bad. Arrangements completed to evacuate approximately 300 of the most serious cases to [the hospital] nearby.... Water sufficient for one-third of camp's needs is available and being furnished from Weimar. The water pumping stations are presently being repaired and full water service should be restored in 48 hours.... "

How these arrangements affected the 183rd was captured in one of Scott's photos that appears in the pamphlet with the caption, "Some children and sick leaving Buchenwald - loading in some of the vehicles of 183rd Engineer Combat Battalion." In his narrative Scott writes, " We eventually left after helping to remove some of the survivors for medical assistance."

A number of Holocaust survivors from Buchenwald have testified to their encounters with African-American soldiers on that day. Survivor David Yager has stated that the first American soldier he saw was Sgt. Leon Bass. "Everybody was screaming.... The soldiers came closer and closer and stopped in the middle of where we used to go out for counting." It wasn't until years later, in the United States, that Yager would learn Bass's name. Survivor Dr. Henry Oster has remarked on the high sensitivity displayed by the African- American soldiers in their encounters with survivors. The African-American soldiers could hardly overlook the irony of their own status in an Army that considered them inferiors, even as they fought to defeat the Nazi army carrying the banner of racial supremacy. Black Soldiers must have felt a unique spiritual kinship with the holocaust victims that they encountered in those camps.

Dr. Henry Oster recalled, "I was seventeen, and I was kind of weak. I came out of the barracks and we were confronted by the absence of Germans. And then we saw people we had not seen before. The oddest thing was that they were Black. Convoys of Black and white soldiers came through. They brought food and, strangely enough, the Black soldiers were inherently much more generous with food and clothes than the white soldiers were. This was on April 11th, or the day after. It was the day Roosevelt died".

Survivor Ivar Segalowitz also recalls Roosevelt's death (April 12th, 1945) as a critical point in time. He has stated that he was virtually dead, but conscious enough to be aware of both his liberation and of Roosevelt's death. He said, "I knew I had been liberated, but I couldn't move. I was stuck in my bunk. My friends told me. I was carried out on a stretcher by a Black soldier."

The Testimony of survivors Dr. Henry Oster and Ivar Segalowitz is consistent with records that place the arrival of the 183rd Eng. C Bn. on April 12, 1945, the second day of the liberation of Buchenwald.

Survivor Alex Gross of Atlanta, Ga. became a personal friend of Scott in later years. In a conversation I had with Mr. Gross he remarked on the agony that Scott had expressed over the controversy of the 183rd's arrival at the Buchenwald camp. Alex recalled that Scott had said he made no personal record of the date at the time. So when Scott put together his pamphlet, he adopted the official date of the liberation, April 11th, 1945. He knew they were there very early, because of the emergency functions his unit had engaged in. The fond memories the Buchenwald survivors have for their African American liberators was heightened by the fact that the 183rd was clearly engaged in life-sustaining functions at Buchenwald. The Engineers' role in emergency evacuation of the critical ill and their service to meet the water needs of the camp was critical to the survival of many inmates after the discovery of the camp. Alex Gross has expressed the concern, "Please do not permit a mockery to be made of the fact that black troops were involved in the liberation of the camps."

I am pleased to write this article for the paper founded by the father of William A. Scott III and to provide the Atlanta Daily World with the first exposure to the records sustaining Scott's arrival at Buchenwald on the second day of its liberation. As a first cousin to Scott, I am honored that I was given an opportunity to present these findings at the Auburn Avenue Research Library on African-American Culture and History and to donate the records to the library in the name of The William A. Scott Holocaust Education Fund.

The official definition of "liberators", as set forth by the U.S. Army Center of Military History and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Council in 1992, is as follows: "LIBERATOR" DEFINITION: The Center and the Council agreed that eligibility for liberation credit would not be limited only to the first division to reach a camp but would include follow-on divisions that arrived at the same camp or camp complex within forty-eight hours of the initial division."

The 183rd Engineer Combat Battalion was not a part of any division, but was a unit of the 8th Corps of General George S. Patton's 3rd Army. Therefore, technically, the official definition of "liberator" discriminates and institutionally excludes the inclusion of this Black unit of WWII from liberator eligibility, regardless of when it arrived at any concentration camp, a fitting epilogue to its service as a segregated unit of the United States Armed forces of World War II.

Dr. Leon Bass has stated in his lectures on the Holocaust: "I came into that camp an angry black soldier. Angry at my country and justifiably so. Angry because they were treating me as though I was not good enough. But [that day] I came to the realization that human suffering could touch us all. ... [What I saw] in Buchenwald was the face of evil... It was racism. "

I am always amazed that I can look back to the namesake of my organization and find a timeless and fitting observation for any occasion in the words of the venerable Frederick Douglass. The lesson Dr. Bass learned that day about the universality of human suffering was expressed in a letter Frederick Douglass wrote to his abolitionist friend William Lloyd Garrison on February 26, 1846. In response to questions by his critics as to why, given the profound plight of his own people, he should expend any of his considerable talents in the cause of others, Douglass wrote:

Though I am more closely connected and identified with one class of outraged, oppressed and enslaved people, I cannot allow myself to be insensible to the wrongs and sufferings of any part of the great family of man. I am not only an American slave, but a man, and as such, am bound to use my powers for the welfare of the whole human brotherhood.